Huzzah! The Admiral's Men Are Returned To The House!

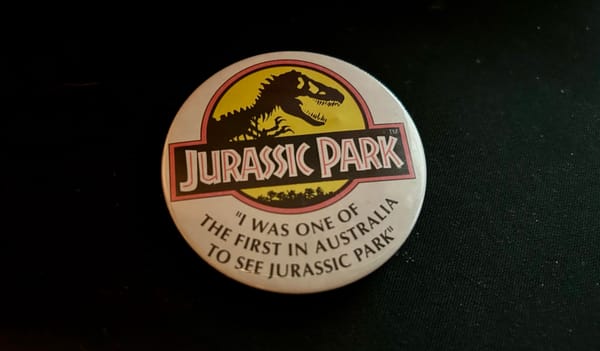

Once upon a time, I was a freelance writer. (See above for evidence.)

Ten or fifteen years ago, there were numerous opportunities to place culture writing (that is, essays and reflections not pinned to or timed for a glancingly brief window of "relevance" designed to maximise "impact") in the Australian press. In the glory days of local digital media, one could pitch--for example--a meandering essay about how losing your virginity on Neighbours is a one-way ticket to the grave ("All Sluts Go To Heaven", written for The Vine), or a listicle about how to make your interior design reflect the post-apocalyptic hellscape of Mad Max: Fury Road ('Mad Max: Fury Road home decor inspiration', written for Domain), and someone would pay you to write it.

Looking back on this extraordinarily productive time in my career (some weeks I would publish four or five pieces), it's clear that while it was proof of the almost utopian freelance budgets at the time, it was also fuelled almost entirely by my as-then undiagnosed Autism: every piece was sparked by hyperfocus and run through with enthusiastic connections between seemingly disparate ideas - what Paul Heilker and M. Remi Yergeau refer to as a ‘remarkable ability to find points of intersection between divergent data sets’.

It will amaze you to hear that special-interest-based journalism is not in hot demand in today's media landscape, and neither is Autistic writing - that is, writing that is Autistic in nature, not just "about" it. (I mean, you could also argue that writing is not in hot supply in the Australian media and you wouldn't be off the money.) Autistic writing is, by many metrics, "wrong": too many ideas, too much language partitioning, endless sentences, burying the lede, peppered with malapropisms, overflowing with segues; as Yergeau would put it, ‘[p]ointing or gesturing too much, and with too much enjoyment, and with too much of the too much too much’. Or, in Steacy Easton's beautiful words, the uniquely Autistic manner of ‘exchanging facts, exchanging the taxonomic list [in] an act of solidarity and intimacy’. The info-dump is one of the Autist's most reviled behaviours - the notion, as I wrote in my book, Late Bloomer, that you don't make friends with steam train facts. Well, fuck that. Hence this project's title: The Monologue.

'To imagine an autistic rhetoric or an autistic literature,' Michael Berubé wrote in the Sydney Review Of Books, 'is to struggle, audaciously, against a legacy of neurotypical people failing to imagine autism as anything other than lack.' I am no longer particularly interested in writing to/through the non-Autistic gaze. Not Autistic? Nut up: autie-ethnography, as Robert Rourke observes, offers the reader 'an affective sense of Autism'.

For some time now, I've felt a yearning for the days when I could get these ideas out of my head and share them with the world. I resisted Big Newsletter for as long as possible, but as the online realm has become increasingly beset with slop, and countless publications have folded, narrowed their remit, tightened their budgets, and/or failed the moral test of accurately reporting on Israel's genocide in Palestine, maintaining my own ~independent "publication" seems the only way to go.

Please subscribe to receive emails when new content is published, and to support my work... whatever that turns out to be.

PS The Monologue retains a convention my dearly departed TinyLetter began, and my Phd continued, of using movie quotes as titles. Here's an excerpt from my thesis that explains this approach:

The chapter subheadings all begin with a line from a Hollywood action movie that, in my associative, echolalic thinking, speaks to what each section explores. For example, ‘Not A Monopoly. More Of A Controlling Interest’ introduces my examination of screenwriting manuals in the second section of this exegesis. The line is from a scene in Tenet (2020) where former CIA agent The Protagonist (John David Washington) meets with Sir Michael Crosby (Michael Caine), a British intelligence officer. Sir Michael informs The Protagonist that he will need to improve his wardrobe if he plans to pass undetected in the upper echelons of London society. As Sir Michael tosses him an American Express Black Card, The Protagonist sniffs, ‘You British don’t have a monopoly on snobbery, you know,’ to which Sir Michael responds, wryly, ‘Well, not a monopoly. More of a controlling interest.’ For me, the quote refers both to screenwriting manuals’ ‘controlling interest’ in dictating screenwriting best practice and to notions of masking. Like The Protagonist, I have to mask in order to abide by these orthodoxies and pass as non-Autistic.

[...]

If I am speaking with someone, they may say a word or mention something that will “light up” a response in my mind’s catalogue of facts and quotes; my taxonomic list. Sharing these points of intersection—which, in my experience, often come in the form of echolalic quotes from movies, or tangential facts—is nearly impossible for me to avoid; it can be almost physically uncomfortable.